Zoom in and explore the northern boreal forests of western Canada on Google Earth and you’ll see long straight lines making their way through the forest. These lines are cleared trails through the forest to extract resources, creating roads for forestry and seismic lines searching for underground oil and gas deposits.

Now picture yourself faced with the task of moving across this landscape: Will you push your way through dense trees and underbrush, or will you choose to walk on the trails?

Like humans, wolves often choose the path of least resistance, moving faster and farther on human-created trails through the forest. Increased wolf movement is believed to play an important role in the decline of the threatened boreal woodland caribou—an iconic species in Canada (just look at the quarter in your pocket).

When wolves move farther, they encounter their prey more frequently, and caribou are being hunted by wolves at rates they cannot sustain.

(Natasha Crosland/Caribou Monitoring Unit), Author provided

Smaller territories

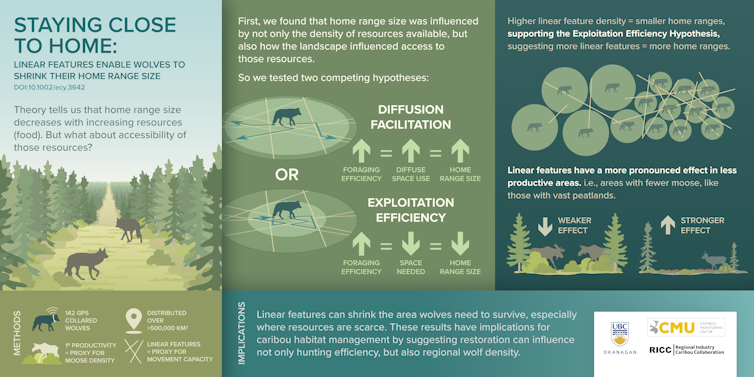

But now, we’ve also found that wolves living in areas that make it easier for them to get around need less space to make a living. The relationship is particularly strong when prey are scarce.

We tracked 142 wolves using GPS collars across British Columbia, Alberta and Saskatchewan—spanning over 500,000 square kilometres. The tracked wolves spanned areas with low to high prey density (measured using a metric of habitat productivity, or how much vegetation there is for species like moose), and had varying access to human-created trails.

Wolves living in areas with high densities of human-created trails took up an area roughly 20 times smaller than wolves without trails, but only when they lived in areas with low habitat productivity. Comparatively, trails didn’t change the area needed for wolves when they lived in areas with high habitat productivity.

(Created by FUSE for Caribou Monitoring Unit/UBC-Okanagan/Regional Industry Caribou Collaboration), Author provided

Think about picking berries. If the berries are hard to find, you have to go looking far and wide to get enough to fill up your basket. But if something makes it easier for you to find the berries, then you don’t have to look around as much. You can just grab all the ones that you see close to you. The advantage of being able to easily find berries would be less important if there are a lot because you can skip over a few without noticing. But it becomes more important when there are few to begin with, and every last berry counts.

This is exactly what we are seeing with wolves: Instead of choosing to travel far and wide, wolves with access to lots of trails stay close to home and get by with what they have.

Watch: Tiny wolf pups practice howling together

The space animals use to carry out their lives is called a home range, or if defended from conspecifics like in the case of wolves, a territory. If animals have smaller home ranges, that means more animals can crowd into a given space, increasing the density of that species. It is well documented that animals need less space when there is an abundance of food around—and now we know that easier access to that food can also decrease home range size. We found that increasing a wolf’s access to their prey, through things like cleared trails through the forest, can decrease their home range size, likely increasing the regional density of wolves.

Habitat restoration

But why do we care about how big wolf home ranges are? One of the biggest conservation challenges in Canada is that of woodland caribou. Caribou live across large areas, overlapping places where the energy and forestry sectors are actively extracting natural resources like oil, gas and timber.

(Melanie Dickie/Caribou Monitoring Unit), Author provided

Habitat restoration and protection have been identified as key steps needed to recover declining populations. Despite existing efforts and policies, caribou habitat loss continues to accelerate across much of western Canada.

Habitat restoration is imminently needed, but is expensive and time consuming. Prioritizing habitat restoration in areas where it will be most beneficial to caribou as soon as possible is necessary for effective caribou management.

Habitat restoration has two main goals: to reduce wolf hunting efficiency by limiting their use of trails and slow their movement when on them and to return the forest to caribou habitat. But now we have reason to believe that slowing wolves down can also reduce wolf density on the landscape — forcing individual wolves to take up more space and push others out—especially in low-productivity peatlands, where the effect on home ranges is stronger.

Effective habitat restoration is going to be important for moving away from other management actions like wolf management in the long term. But, we have a lot of work ahead of us. There are hundreds of thousands of kilometres of these cleared trails that need to be restored. Our study points us towards prioritizing low-productivity areas to see the biggest effects sooner.![]()

Melanie Dickie, PhD candidate, Biology, University of British Columbia

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Read more: Photographer captures rare images of coastal wolf